Contents

We need a library for that…

Underscore.js to the rescue

Performance

Language independent concepts

Functional programming

Underscore.js: under the hood

Alternatives

Summary

We need a library for that…

Before looking at Underscore.js more closely let’s first discuss the context in which it can be useful. We will see what problems we may have and that it actually solves them well. Because, who knows maybe we don’t need Underscore.js at all and you can already stop reading the article?

Here is our problem. Let’s say that as part of some other larger project we would like to write code that analyzes text and outputs some important information like the list of all the used words in the alphabetical order, the top 10 most frequently used words, the total number of words, etc.

This is what our first attempt at solving the problem might look like if we never heard of functional programming in general and Underscore.js and corresponding JavaScript APIs in particular.

The text we would like to analyze:

var text = "Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting \ by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once \ or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, \ but it had no pictures or conversations in it, \ 'and what is the use of a book,' thought Alice \ 'without pictures or conversations?'\ \ So she was considering in her own mind (as well as she could, \ for the hot day made her feel very sleepy and stupid), whether \ the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble \ of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a White \ Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.";

And the code that analyzes the text:

function textWords(text) {

var words = text.match(/[a-zA-Z\-]+/g);

for (var i = 0; i < words.length; i++) {

words[i] = words[i].toLowerCase();

}

return words;

}

function wordsFrequencies(words) {

var frequencies = {},

currentWord = null;

for(var i = 0; i < words.length; i++) {

currentWord = words[i];

frequencies[currentWord] =

(frequencies[currentWord] || 0) + 1;

}

return frequencies;

}

function sortedListOfWords(wordsFrequencies) {

var words = [];

for (var key in wordsFrequencies) {

if (wordsFrequencies.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

words.push(key);

}

}

return words.sort();

}

function topTenWords(wordsFrequencies) {

var frequencies = [],

result = [];

for (var key in wordsFrequencies) {

if (wordsFrequencies.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

frequencies.push([key, wordsFrequencies[key]]);

}

}

frequencies = frequencies.sort(function(freq1, freq2) {

return (freq1[1] < freq2[1])

? 1

: (freq1[1] > freq2[1] ? -1 : 0);

});

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

result[i] = frequencies[i];

}

return result;

}

function analyzeText(text) {

var words = textWords(text),

frequencies = wordsFrequencies(words),

used = sortedListOfWords(frequencies),

topTen = topTenWords(frequencies);

console.log("Word count = ", words.length);

console.log("List of used words = ", used);

console.log("Top 10 most used words = ", topTen);

}

analyzeText(text);

This should be self explanatory, but still let’s look at one of the methods more closely, in particular we will be interested in low level implementation details:

function wordsFrequencies(words) {

var frequencies = {},

currentWord = null;

for(var i = 0; i < words.length; i++) {

currentWord = words[i];

frequencies[currentWord] =

(frequencies[currentWord] || 0) + 1;

}

return frequencies;

}

Here we just iterate through the list of all words and for each word increment its frequency value stored in frequencies. Note, that this implementation contains the details how we exactly increment the index when getting the next word and this is pretty low level. It is first not important to our implementation and second very likely can be reused in many other use cases. This is precisely the reason why JavaScript has it already abstracted into a separate function Array.prototype.forEach. Let’s rewrite wordsFrequencies using this function instead:

function wordsFrequencies(words) {

var frequencies = {};

words.forEach(function(word) {

frequencies[word] = (frequencies[word] || 0) + 1;

});

return frequencies;

}

No doubt the implementation became somewhat clearer without an extra index variable i and currentWord. But actually even this version can be made shorter and the low level implementation details of how exactly frequencies changes with each processed word can also be partially hidden. For that we will use the Array.prototype.reduce function:

function wordsFrequencies(words) {

return words.reduce(function(frequencies, word) {

frequencies[word] = (frequencies[word] || 0) + 1;

return frequencies;

}, {});

}

It seems like we improved this part quite a bit. But now we notice that in another place of our code we read the list of all the keys of an object, and there is also a separate Object.keys function provided by JavaScript to do that, and instead of:

for (var key in wordsFrequencies) {

if (wordsFrequencies.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

frequencies.push([key, wordsFrequencies[key]]);

}

}

we can write:

frequencies = Object.keys(wordsFrequencies).map(function(key) {

return [key, wordsFrequencies[key]];

});

Much more readable. And here we also used the Array.prototype.map function.

Now below is the whole version of our program rewritten using the JavaScript standard methods we mentioned above:

function textWords(text) {

return text.match(/[a-zA-Z\-]+/g).map(function(word) {

return word.toLowerCase();

});

}

function wordsFrequencies(words) {

return words.reduce(function(frequencies, word) {

frequencies[word] = (frequencies[word] || 0) + 1;

return frequencies;

}, {});

}

function sortedListOfWords(wordsFrequencies) {

return Object.keys(wordsFrequencies).sort();

}

function topTenWords(wordsFrequencies) {

var frequencies = [],

result = [];

frequencies = Object.keys(wordsFrequencies)

.map(function(key) {

return [key, wordsFrequencies[key]];

}).sort(function(freq1, freq2) {

return (freq1[1] < freq2[1])

? 1

: (freq1[1] > freq2[1] ? -1 : 0);

});

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

result[i] = frequencies[i];

}

return result;

}

function analyzeText(text) {

var words = textWords(text),

frequencies = wordsFrequencies(words),

used = sortedListOfWords(frequencies),

topTen = topTenWords(frequencies);

console.log("Word count = ", words.length);

console.log("List of used words = ", used);

console.log("Top 10 most used words = ", topTen);

}

analyzeText(text);

The program became shorter and much more clear. However, if we look carefully, we can notice that there are still a few places with lots of low-level details, for example:

function topTenWords(wordsFrequencies) {

var frequencies = [],

result = [];

frequencies = Object.keys(wordsFrequencies)

.map(function(key) {

return [key, wordsFrequencies[key]];

}).sort(function(freq1, freq2) {

return (freq1[1] < freq2[1])

? 1

: (freq1[1] > freq2[1] ? -1 : 0);

});

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

result[i] = frequencies[i];

}

return result;

}

still has low level details related to sorting and getting the first 10 elements.

Moreover this function clearly does too much at once and almost asks to split it in two functions. And having 10 hardcoded in the body of the function is clearly far from perfect. Notice that this became much more evident only after we partially re-factored the code of the original function and abstracted away some of the implementation details. For now we will stop here with our re-factoring and return to this function later when we will use Underscore.js in the process.

Unfortunately the standard JavaScrit, while providing a number of useful functions such as map, reduce, filter, etc. still lacks some other functions and the API is a bit limited.

For example in the case of topTenWords function above we miss the function for taking first n elements from an array which is quite common to many languages, see take from the standard Clojure library or take from the standard Ruby library.

This is where Underscore.js comes to the rescue.

Underscore.js to the rescue

Underscore.js can be installed as a Node module:

npm install underscore

Or you can just include the minified source on your page:

<script src="http://documentcloud.github.com/underscore/underscore-min.js"> </script>

The source code for the library can be found on Github github.com/jashkenas/underscore

Underscore.js does just what we need: it provides a large number of convenient functions that we can use to get rid of low level implementation details in our programs. There is some intersection with the standard JavaScript API, but Underscore.js provides far more useful functions than we can find in the standard JavaScript. For example, the last function we considered for getting the top 10 frequent words can be rewritten as follows:

function wordsAndFrequenciesDescending(wordsFrequencies) {

return _.sortBy(_.map(_.keys(wordsFrequencies),

function(key) {

return [key, wordsFrequencies[key]];

}),

_.property("1")).reverse();

}

function topWords(wordsFrequencies, number) {

return _.take(

wordsAndFrequenciesDescending(wordsFrequencies),

number

);

}

Notice that it is now more terse and expressive. _.keys corresponds to Object.keys, _.map to Array.prototype.map we encountered before, etc. Also we see that Underscore.js does include the take method we mentioned before and which was missing from the standard JavaScript API. The function by which we sort became much shorter and clearer as well thanks to using the _.property function provided by Underscore.js.

Another thing that we immediately notice about Underscore.js is that rather than adding methods to JavaScript objects, Underscore.js provides external methods that take an object as a parameter.

Underscore.js also allows to use a more object-oriented style by wrapping an object and making its functions available on the resulting wrapper object as methods. When invoked each such method returns another wrapper object that contains the intermediate computation result and on which we can again invoke Underscore.js methods. This way we can chain computations.

For example, compare:

var object = {

"key1": "value1",

"key2": "value2",

"key3": "value3"

};

_(object).keys();

_.keys(object);

Both ways of calling keys in this case are valid. You can read more about wrapping objects with Underscore.js and chaining in the documentation.

And here is the full version of our initial program rewritten using Underscore.js functions.

function textWords(text) {

return _.map(text.match(/[a-zA-Z\-]+/g), function(word) {

return word.toLowerCase();

});

}

function wordsFrequencies(words) {

return _.reduce(words, function(frequencies, word) {

frequencies[word] = (frequencies[word] || 0) + 1;

return frequencies;

}, {});

}

function sortedListOfWords(wordsFrequencies) {

return _.sortBy(_.keys(wordsFrequencies));

}

function wordsAndFrequenciesDescending(wordsFrequencies) {

return _.sortBy(_.map(_.keys(wordsFrequencies),

function(key) {

return [key, wordsFrequencies[key]];

}),

_.property("1")).reverse();

}

function topWords(wordsFrequencies, number) {

return _.take(

wordsAndFrequenciesDescending(wordsFrequencies),

number

);

}

function analyzeText(text) {

var words = textWords(text),

frequencies = wordsFrequencies(words),

used = sortedListOfWords(frequencies),

topTen = topWords(frequencies, 10);

console.log("Word count = ", words.length);

console.log("List of used words = ", used);

console.log("Top 10 most used words = ", topTen);

}

analyzeText(text);

The functions became much more succinct and clear and the low level implementation details are now well hidden.

Actually, it is possible to make (thanks for pointing this out, rooktakesqueen) the code even more expressive. Using the _.chain function we can re-write wordsAndFrequenciesDescending as follows:

function wordsAndFrequenciesDescending(wordsFrequencies) {

return _.chain(wordsFrequences)

.keys()

.map(function(key) {

return [key, wordsFrequencies[key]];

})

.sortBy(_.property('1'))

.reverse()

.value();

}

And… That’s it, if you have managed to follow the article this far, you already have a good grasp of what Underscore.js is and how it can help you with writing your code. You can always get more information about Underscore.js by reading its annotated source code or documentation. The number of provided functions is considerably larger than what we discussed so far, in particular there are separate functions for objects, arrays, collections and functions, as well as a few generic utility functions.

Even more functions can be found in underscore-contrib. Although the functions there may be less generic and suitable only for a particular type of problems. If you cannot find some function in Underscore.js, check it out, it may already contain what you need. But this part is out of the scope of the present article.

What follows below is more detailed discussion about the style of programming promoted by Underscore.js, performance, implementation details of the library, etc. Read it if you would like to have more advanced understanding of the library.

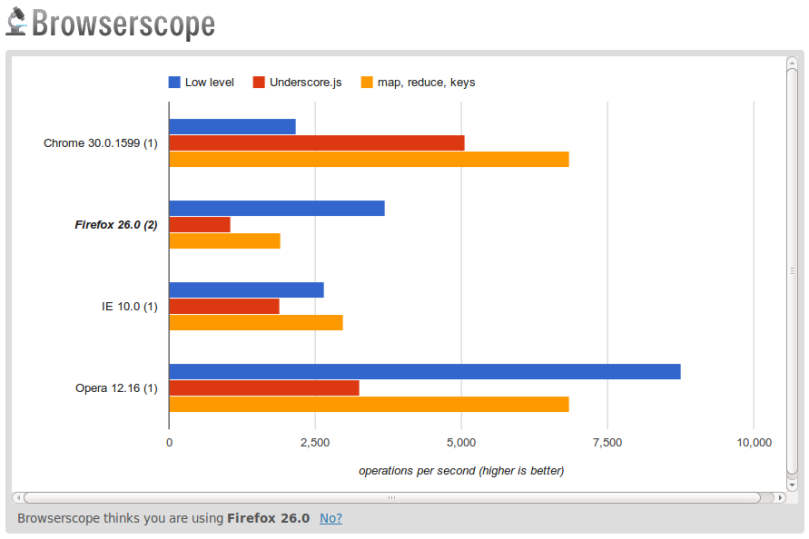

Performance

Underscore.js provides us high level abstract functions that make our code clearer and shorter, that is it makes us as developers more productive, but what about the computer productivity? Is our code performant enough? Let’s use jsperf to test that in our case and see some results for the three implementations above:

Here is the link to the test cases and the full results http://jsperf.com/underscore-js-vs-map-reduce-keys-vs-low-level

We immediately see that using the native map, reduce and keys is from 1.5 to 2 times faster than the Underscore.js version.

Suprisingly enough in the case of our program for Chrome and IE10 using native map, reduce and keys is even faster than the low level implementation. But actually it does make sense, because those native methods are implemented as native code which is somewhat faster than trying to write the same logic in JavaScript.

Although this does not always seem to be true, and the low level implementation can still be much faster than the native forEach and reduce if the arrays are large enough and contain only numbers as another benchmark demonstrates http://jsperf.com/foreach-vs-reduce-vs-for-loop

The main result here is that the performance of all the three approaches is of the same order, i.e. is comparable. Then if we get more readability with Underscore.js or native functions we probably should use them as we do not loose much in performance and in the case of Chrome we actually win.

Based on this benchmark the recommendation will be consider avoiding writing your own loops, as they are much less expressive, more complicated and do not always guarantee better performance.

If you still have doubts, in general, when performance considerations enter your decision making, please, remember, as a rule we should optimize only the 10% of the code that takes 90% of the execution time, otherwise we are wasting our development time, do not win much performance-wise and make our code unnecessary complicated.

Language independent concepts

If you are familiar with any other languages than JavaScript you might have seen already something similar to the functions we used above. Ruby has its Enumerable module which defines many of the similar methods, Java has Guava and in fact almost everybody in the Java world tries to develop their own version of Underscore.js without even sometimes realizing it, Scala has many of these methods included into the standard library, etc.

If you look carefully at what we discussed so far, you will see that there is not much that is JavaScript specific. We just talked about collections, functions, passing functions into other functions and creating higher level functions, that is functions that can accept other functions as arguments. In fact, we can define functions like map, filter, reduce, etc. in any other language that has the concepts mentioned above.

A large part of the philosophy and ideas behind Underscore.js is thus language independent and quite generic. But of course, in order to be practically useful it also has a sizable JavaScript-specific part which is still needed by JavaScript developers, for example, take a look at the _.toArray and _.isDate functions.

That ideas and philosophy are in large part inspired by Functional Programming (FP), which is a development paradigm that views functions as the primary building block of programs.

For some languages that currently do not treat functions as important enough, for example, Java, it is stil possible to emulate passing functions into functions and create something similar to Underscore.js but it will look much uglier and will be quite cumbersome to use, for example, compare the different versions of a program that converts a collection of strings into a collection of lengths of each string:

the Java version (using the Functional Java library):

Array.<String, Integer>map().f(new F<String, Integer>() {

@Override

public Integer f(String arg) {

return arg.length();

}

}).f(array("a", "ab", "abc")).array(Integer[].class));

the Scala version:

Array("a", "ab", "abc").map(_.length())

the Ruby version:

["a", "ab", "abc"].map {|str| str.length}

and the JavaScript one:

["a", "ab", "abc"].map(function(str) {

return str.length;

});

Now it is clearly time for a bit of critism in the direction of JavaScript. You can see that while JavaScript version is comparable to the Scala one it is still a bit more wordy and includes syntactic noise such as function and return keywords. But here Underscore.js will not help us much, as we cannot easily circumvent the core language limitations. And we can only feel sorry for poor Java developers until they finally get lambdas in Java 8.

Functional programming

This is a generic programming paradigm in which the primary (or at least one of the primary) building blocks that are used to create new programs are functions.

Another things often talked about in relation to Functional Programming (FP) are immutability and referential transparency.

We will not go into many details what those mean, and provide only a brief explanation, but please, feel free to take a deep dive and explore more on your own.

In a couple of words the basic principles of FP can be summed up as follows:

- You can substitute a function invocation with the body of the function withouth changing the results of the computation (referential transparency)

- There is no shared state in the program, functions accept as arguments and produce immutable objects

- There is no notion of time, the actual scheduling of when various parts of the program will be evaluated does not affect the results of the computation as long as each function gets all of its arguments before its invocation

- Functions can be passed as arguments into other functions and can be returned from functions (in other words, functions are “first-class citizens”)

The programs in FP are more like mathematical statements or formulas then a set of imperative instructions that should be executed one by one.

Many of the languages considered “functional” do not follow all of the outlined principles to begin with. For example, even in Scala it is possible to have mutable shared state although there is considerable language support for immutability. Quite often the theoretical beauty of FP has to make some room for practical concerns: writing something to disk or sending a network message obviously do require to have the notion of time in programs.

It is relatively clear that JavaScript only satisfies the last requirement. We can of course try to create programs that have no shared state and will be referentially transparent in JavaScript but it will require additional efforts from our side as the developers and we are not restricted to violate those principles by the language itself.

That said, having functions as “first-class citizens” in JavaScript is actually quite a powerful feature already. It moves us considerably in the direction of FP, and we can always try to follow the rest of the principles of FP when it suits us best. Definitely Underscore.js provides a great deal of help here.

Underscore.js: under the hood

Let’s now take a look at the implementation details of Underscore.js. There we can find some good examples of functional style of programming but normally the library tries to avoid using its own functions when implementing other functions because of the performance concerns, so some of the examples we will see will be what we call here “low-level”. And this is perfectly acceptable because many libraries depend on Underscore.js and here the performance actually does play an important role, it is even probably more important than readability.

The full source code of Underscore.js is available in the github repository https://github.com/jashkenas/underscore

One example of the functional approach used in Underscore.js is the union function:

_.union = function() {

return _.uniq(_.flatten(arguments, true));

};

The implementation clearly explains what the function does: given a few arrays it first concatenates those arrays with _.flatten and then removes non-unique elements with _.uniq.

Another good example of the functional style is a number of functions that deal with grouping, let’s look at the code for _.groupBy:

// An internal function used for aggregate "group by" operations.

var group = function(behavior) {

return function(obj, iterator, context) {

var result = {};

iterator = lookupIterator(iterator);

each(obj, function(value, index) {

var key = iterator.call(context, value, index, obj);

behavior(result, key, value);

});

return result;

};

};

// Groups the object's values by a criterion. Pass either

//a string attribute to group by, or a function that

//returns the criterion.

_.groupBy = group(function(result, key, value) {

_.has(result, key)

? result[key].push(value)

: result[key] = [value];

});

group is quite an interesting function. It accepts another function that alters its behavior and then returns a function that accepts an object and an iterator. The third argument context is optional, it can specify on which object the iterator should be invoked, i.e. the value of this inside the iterator function. This function returned from group when it is invoked calls the provided iterator to get the key for each value it gets from the target object on which it was invoked. If object is an array, then value will be an element of that array. Once we have key and value we use the provided behavior to process them and maybe alter the result which we first initialize to an empty object. In the end we return result.

We call functions that accept other functions as arguments “higher-order” functions. Then, speaking in the language of Functional Programming, group is just a higher-order function that returns another higher-order function once it is invoked.

This may sound too complicated, but once we look at a concrete example of how _.groupBy is defined and used, everything becomes much clearer.

We see that _.groupBy is just a function returned by the group function which we customize with a specific behavior that for each key and value pushes that value into the array of values stored in result[key]. This way we get all the values stored in the result grouped into corresponding arrays which can be accessed as properties on the result object.

An example of how the _.groupBy function is used:

//Result: {"even":[0,2,4],"odd":[1,3]}

_.groupBy([0, 1, 2, 3, 4], function(value) {

return (value % 2 == 0) ? "even" : "odd";

});

Here we provide the concrete iterator function that specifies how to map each value to a key. In this case this is a function that determines for each value whether it is odd or even.

The rest of the grouping functions _.indexBy and _.countBy are defined in a very similar fashion:

// Indexes the object's values by a criterion, similar

// to `groupBy`, but for when you know that your index

// values will be unique.

_.indexBy = group(function(result, key, value) {

result[key] = value;

});

// Counts instances of an object that group by

// a certain criterion. Passeither a string attribute

//to count by, or a function that returns the criterion.

_.countBy = group(function(result, key) {

_.has(result, key) ? result[key]++ : result[key] = 1;

});

You can actually see what they do by doing an analysis of code similar to what we have just done with _.groupBy.

But as we mentioned not everything in Underscore.js is written in a functional style. An example of this is the _.object function that allows to create an object from provided arrays of properties in two ways:

//Result: {"key1": "value1",

// "key2": "value2", "key3": "value3"}

_.object([

["key1", "value1"],

["key2", "value2"],

["key3", "value3"]

]);

//Result: {"key1": "value1",

// "key2": "value2", "key3": "value3"}

_.object(["key1", "key2", "key3"],

["value1", "value2", "value3"]);

The current implementation is as follows:

_.object = function(list, values) {

if (list == null) return {};

var result = {};

for (var i = 0, length = list.length; i < length; i++) {

if (values) {

result[list[i]] = values[i];

} else {

result[list[i][0]] = list[i][1];

}

}

return result;

};

Which is quite low level and complicated. If we were to rewrite this using the functional style, we would get a shorter and cleaner version:

_.object = function(list, values) {

if (list == null) return {};

var pairs = values

? _.zip(list, _.take(values, list.length))

: list;

return _.reduce(pairs, function(result, pair) {

result[pair[0]] = pair[1];

return result;

}, {});

};

But this version turns out to be almost 10 times slower because of using of the _.zip and _.take functions which are themselves a bit slow. In the end we sacrifice the readability and functional purity for the performance and choose to leave the current implementation in place. The corresponding performance test that demonstrates the comparative performance of the two implementations

can be found here http://jsperf.com/underscore-object-implementations

Here we will stop with exploring the internal workings of Underscore.js as the parts of the library that we reviewed are already quite representative, but feel free to review the rest of the code.

Alternatives

There are a number of alternative helper libraries or APIs that you can use, but Underscore.js is by far the most popular one and the one where you can count on good support and the availability of the need features. De-facto this library has become a standard, for example, it is the most dependent upon Node module.

But as we have seen among the drawbacks may be a bit of a loss of the functional purity in the implementation, large API and slightly worse than native performance. Also not everybody can like the default Underscore.js style when we have to execute external functions on each object. And surely there are always alternatives.

One of them is the Lo-Dash library (thanks jcready for the reference). Personally I did not use it much, but it looks quite interesting and seems to do all of the things that Underscore.js does and sometimes even a bit more. A quick benchmark http://jsperf.com/reduce-underscore-js-vs-lo-dash shows that _.reduce is 2 times faster in Lo-Dash than in Underscore.js when the benchmark is run in Chrome, but at the same time in Firefox the two libraries do not have noticable performance differences.

Yet another alternative you may consider is Lazy.js (thanks brtt3000), it seems to be the fastest library available based on the benchmarks provided on its site comparing it both with Underscore.js and Lo-dash. If your main concern is performance you may give this library a try.

Also you can always just use the native methods analogous to those provided by Underscore.js: map, reduce, filter, etc. Modern browsers support them well and Underscore.js itself falls back to the native implementations for its functions when it is possible for performance reasons. But be mindful that the performance win will not be more than 50% – 100% which can be relatively insignificant if the hot spots of your application lie elsewhere.

If you want to have a small core of well-defined functions and more of a functional paradigm, then consider using, for example, fn.js https://github.com/eliperelman/fn.js, a “JavaScript library built to encourage a functional programming style & strategy.”

Summary

We have seen that:

- Writing our own loops and low level code makes our programs less readable and not always faster

- Instead the native higher-order functions should be used or a specialized library like Underscore.js

- With Underscore.js the resulting code is much more maintainable, as a result the development productivity grows

- The performance cost of using Underscore.js is acceptable in most cases

- It would be good to include functions similar to some of the Underscore.js functions into the language standard and support them natively

If you find yourself writing many loops and iterating over arrays a lot in your project you should definitely give Underscore.js a try and see how your code improves.

The code examples from this article can be found on github github.com/antivanov/misc/tree/master/JavaScript/Underscore.js

Links

Underscore.js

Lo-Dash

Lazy.js

“Functional JavaScript: Introducing Functional Programming with Underscore.js” book

this is such a great write-up. thanks!

Great writeup… could you elabourate on adding Underscore.js methods directly to an object? I am trying to understand why the _(object) syntax works as an alternative to _.method(object).

Hi. I corrected that part, it was a bit misleading. In fact we do not add methods directly to an object but wrap it into another object. The wrapper object has all the Underscore.js functions defined as its methods and each such method returns a similar wrapper object which allows to chain invokations like is shown in the documentation http://underscorejs.org/#chaining

[…] Page bloat update: The average web page is more than 2 MB in size Lo-Dash and JavaScript Performance Optimizations – John-David Dalton Lodash: 10 Javascript Utility Functions That You Should Probably Stop Rewriting Eloquent Javascript with Underscore.js […]